Quick Takeaways:

The English language has a rich history of borrowing words from other languages, especially from Latin. Latin abbreviations such as ‘a.m.’, ‘p.m.’ and ‘CV’ have become part of our everyday vocabulary. Such abbreviations are also frequently used in academic writing, from the ‘Ph.D.’ in the affiliation section to the ‘i.e.’, ‘e.g.’, ‘et al.’, and ‘QED’ in the rest of the paper.

This guide explains when and how to correctly use ‘et al.’ in a research paper.

In previous blogs we have already covered how to write an introduction and literature review, and how to define the purpose and rationale for your study.

Depending on your field, you may need to write your research question and/or hypothesis before moving on to write the main body of your study. You don’t usually need to include both research question and hypothesis, unless you have several hypotheses that arise from the research question.

Important! We are not suggesting that you come up with your research question or hypotheses at this stage:

Your research question or hypotheses should actually have been developed before you conducted or even designed your study.

Here, we’re discussing how you can clearly state the research question or hypotheses.

Your research question, or questions, should specifically state the purpose of your study in terms of the question you aim to answer. Its purpose is to guide and center your research study.

For example:

If the purpose of your study is to evaluate the efficacy of a newly-developed intervention for treating anxiety, your research question might be something like:

“Is intervention A effective for treating people with anxiety?”

The research question above needs to be turned into a testable hypothesis. A hypothesis is a statement rather than a question, and it should make a prediction about what you expect to happen. This is referred to as a directional or alternative hypothesis, and is often abbreviated as H1.

Continuing with the research question example above, the hypothesis might be written as:

“Participants who receive intervention A will show a significant reduction in scores on the Anxiety Scale from baseline to 6-week follow up.”

If your study uses a control group, the hypothesis can be modified to:

“Participants who receive intervention A will score significantly lower on the Anxiety Scale than participants in the wait-list control group.”

Bear in mind that your hypothesis needs to be specific.

Continuing with the earlier example, if your hypothesis only states “Participants who receive the intervention will be less anxious”, it is not specific enough because it does not state how you will know whether anxiety has been reduced or what “less” is in relation to.

When you test a hypothesis, you actually test the null hypothesis, which predicts no difference in the variables you are testing.

Some journals prefer you to state the null hypothesis, often abbreviated as H0, or both the null and alternative.

The corresponding null forms of our example hypotheses are:

“Participants who receive intervention A will show no difference in anxiety scores from baseline to 6-week follow-up.”

“Participants who receive intervention A will show no difference in anxiety scores from participants in the wait-list control group.”

Your research questions and hypotheses are likely to be quite different from our examples depending on the type of your study. We present some examples below for your reference.

Case 1: Experimental study examining the effect of one (or more) independent variable(s) on a dependent variable

Research Question: “Does substance A affect the appetite of rats?”

Directional or Alternative Hypothesis: “Rats that receive an injection of substance A will consume significantly more food than rats that do not receive the injection.”

Null Hypothesis: “Rats that receive an injection of substance A will show no difference in food consumption from those that do not receive the injection.”

Case 2: Correlational study examining the relationships among variables

Research Question: “Does spending time outdoors influence how satisfied people feel with their lives?”

Directional or Alternative Hypothesis: “There is a significant positive relationship between the weekly amount of time spent outdoors and self-reported levels of satisfaction with life.”

Null Hypothesis: “There is no relationship between the weekly amount of time spent outdoors and self-reported levels of satisfaction with life.”

I. It is clearer to the reader if you make the wording for your hypotheses as similar as possible to each other. So, use the same key phrases and terms: rather than making the writing more interesting, varying the use of key terms always causes confusion.

II. Try to position the variables so that the independent variable appears first in the sentence, then the dependent variable. This word order reflects the hypothesised direction of the effect and is therefore clearer than the reverse order.

Wondering why some abbreviations such as ‘et al.’ and ‘e.g.’ use periods, whereas others such as CV and AD don’t? Periods are typically used if the abbreviations include lowercase or mixed-case letters. They’re usually not used with abbreviations containing only uppercase letters.

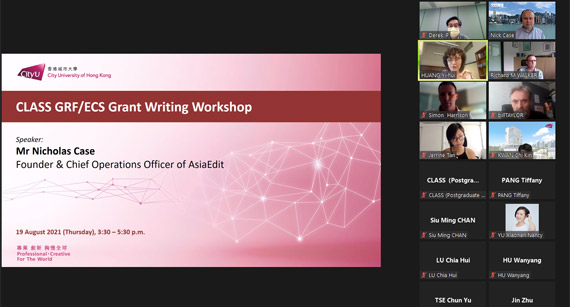

Our latest online workshop built on the success of face-to-face workshops we developed specifically for local universities. Over 30 faculty members joined the session, presented by our Chief Operating Officer, Mr Nick Case, to learn from our case studies on editing research proposals.

The response to our workshop, which included a constructive and insightful Q&A session, was very positive.Drawing on our extensive experience working with hundreds of Hong Kong researchers targeting the GRF and ECS every year, we used examples of poor and subsequently improved proposals to show the attendees how they can make their applications stand out. The response to our workshop, which included a constructive and insightful Q&A session, was very positive.Drawing on our extensive experience working with hundreds of Hong Kong researchers targeting the GRF and ECS every year, we used examples of poor and subsequently improved proposals to show the attendees how they can make their applications stand out. The response to our workshop, which included a constructive and insightful Q&A session, was very positive.Drawing on our extensive experience working with hundreds of Hong Kong researchers targeting the GRF and ECS every year, we used examples of poor and subsequently improved proposals to show the attendees how they can make their applications stand out.

Wondering why some abbreviations such as ‘et al.’ and ‘e.g.’ use periods, whereas others such as CV and AD don’t? Periods are typically used if the abbreviations include lowercase or mixed-case letters. They’re usually not used with abbreviations containing only uppercase letters.

Check out AsiaEdit’s professional research grant proposal editing service.

Read more about our training services covering all aspects of academic writing tailored for local institutions.

More resources on research grant proposal writing: On-demand Webinars

Preparing an effective research proposal – Your guide to successful funding application

Preparing an effective research proposal – Your guide to successful funding application (Part 2)

Rachel first joined us as a freelance editor in 2001, while completing her PhD. After spending a few years as a post-doctoral researcher and then lecturing in psychology, she returned to us in 2010 and focused her career on academic editing. She took on the role of Assistant Chief Editor in 2018, and became co-Chief-Editor in 2020. Unable to leave academia behind completely, she also teaches Psychology at an English-speaking university in Italy, where she is now based. With extensive experience in both academia and publishing, Rachel has an excellent overview of both the client and editor sides of the business.

Your Schedule, Our Prime Concern AsiaEdit takes a personalised approach to editing.

We are East Asia's leading academic editing partner. Established in 1996 and headquartered in Hong Kong, we have strong connections with academics and renowned faculty in the region, built by delivering quality work on schedule for more than 25 years.

Suite 2101, 99 Hennessy Road,

Wan Chai, Hong Kong

9:00am – 6:00pm

(+852) 2590 6588